Amos Wallace was a keeper. So his longtime home on Juneau’s Douglas Island held numerous documents from his nearly 70-year career.

Since he and his wife Dorothy passed away, their son, photographer Brian Wallace, has been going through the collection.

“I was in the basement in the earlier part of this year and I opened up some boxes of stuff and I saw some photos that I’ve never seen before, and unfortunately I found this,” Brian Wallace says.

“This” was a pair of black-and-white, historic photographs showing the elder Wallace with a totem pole he carved in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Both were badly damaged by water.

“I did not want this disaster to happen to the rest of the collection. So I immediately started putting everything together and organizing the archive and then I took it down to Sealaska Heritage [Institute]. And now it’s in a very safe place where it will be preserved for generations,” he says.

The Juneau-based heritage institute preserves and advances Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian culture. It’s planning a new building, the Walter Soboleff Center, to house a growing physical collection, a digital library, classrooms and display space.

That will include the Wallace collection.

“In terms of going out and meeting the rest of the world, Amos was that ambassador for Tlingit people and for Tlingit art,” says Rosita Worl, the institute’s president.

She says Amos Wallace was an important artist and craftsman.

“He definitely brought attention to our art, nationally and internationally,” Worl says.

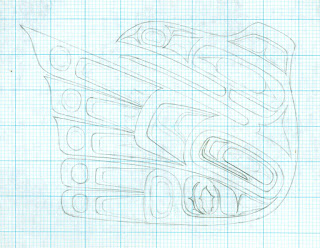

A drawing of a Frog image Amos Wallace created before carving. Image courtesy Brian Wallace and Sealaska Heritage Institute.

“And it certainly takes a person with character to do that,” says Zachary Jones, archivist and collections manager for the institute.

He says Wallace was enthusiastic about his culture and generous with his knowledge.

“He was there showcasing Alaska statehood, as sort of this Alaska Native representative to different people across the nation. [He was] on the Tonight Show, at museums, really sort of an individual teaching the Lower 48 about Alaska Native art,” Jones says.

Jones and Worl say the collection is comprehensive – something that’s not often seen. It includes notes, drawings, photographs and newspaper clippings in Tlingit art.

“You get to see the breadth of the artist’s life. You can see the evolution of his work from an early age to his later years. You can really see the beauty, the depth and aspects of his life that I think we really like to celebrate,” Jones says.

Amos Wallace began carving under the tutelage of his older brother, Lincoln, when he was seven years old. He went to boarding school at the old Wrangell Institute, and studied with respected carver Horace Marks.

He served in the Army in World War II, then spent more than a decade carving small totems with his brother for a Pacific Northwest wholesaler.

As the collection shows, he moved onto a larger stage.

“This is the totem pole that is now in the Brooklyn Children’s Museum,” says Brian Wallace, Amos’ son, as he pulls up a digitized photo from his father’s collection.

“He carved this totem pole in New York City in 1958 for a big department store in Brooklyn called Abraham and Strauss. Several local people in town grew up [there] and said, ‘Hey, yeh, I know that.’ They probably even went and saw my dad carving at one time when they were little kids,” Brian Wallace says.

The elder Wallace did more than carve when he was in New York. He talked to schoolchildren and others about his art, culture and traditions. That led to his “Tonight Show” appearance, back when it was hosted by Jack Paar.

The department store totem later moved to a new location, the Brooklyn Children’s Museum. Brian Wallace pulls up another photo, showing his dad wearing a traditional Chilkat blanket and a woven spruce-root hat.

“This photo was taken the day the totem pole was dedicated. He’s standing there with a little girl and [on cards] he has the Tlingit words for ‘new totem pole’ and words for ‘my country – Alaska’ in Tlingit here,” he says.

The Amos Wallace collection also documents totem carvings at Disneyland, the University of Alaska Fairbanks and museums in Cincinnati, Toronto and Boston.

In addition, the archive includes numerous drawings, such as clan crests, on graph paper. They’re images that became totems, or smaller wooden carvings, or metal jewelry.

“This killer whale here is a common motif he worked on throughout the years. You can see the finished carving of this in the Smithsonian Institution. I’ve seen it in pendants and I’ve seen it in bracelets that he’s made, so this is one of his favorite killer whale designs,” he says. (See more Wallace pieces in the Smithsonian collection.)

Parts of the archive are already digitized. Others wait to be scanned or otherwise preserved for future use.

Worl of the heritage institute says the drawings will be teaching tools. And the whole collection will attract artists and art historians.

“When I look at some of the pieces, I recognize them, as older pieces you don’t see any more. Nowadays the art has gotten more simple, it’s broader. But when you go back and look at the early pieces … I see it in his work,” Worl says.

Parts of the collection are more personal, showing Alaska Native Brotherhood events, or Orthodox Church services. There also are family events, including Amos taking his young son Brian to his first day of kindergarten.

Watch a video of Brian Wallace talking about his father, Amos Wallace, with more photos from his life. Watch below or at this link. It’s from Kathy Dye of the Sealaska Heritage Institute.